The Shapley value was initially proposed in a classic paper in 1953 in the field of game theory and has since been wildly influential in economics. As recent as 2010, the Shapley value was proposed as a feature importance score in predictive models to quantify which features are the most influential for the model output. In the papers listed below, Ghorbani and Zou, propose a different use case in that the aim is to quantify the value of individual data points (not features). There is also literature in estimating Shapley value using Monte Carlo methods, network approximations, as well as analytically solving Shapley value in specialized settings.

Data Shapley: equitable valuation of data for machine learning by Amirata Ghorbani and James Y. Zou et al., ICML’19

What is your data worth? Equitable Valuation of Data by Amirata Ghorbani and James Y. Zou et al.

How to quantify the value of a data point?

If we want to validate data in a supervised machine learning setting, we need three elements, a fixed training dataset $D = {(x_i, y_i)}_i^n$, a learning algorithm $A$, and a performance score function $V (S, A)$, or just $V(S)$ for short (where $ S \supseteq D$).

For an equitable data valuation function, it should satisfy the following three properties:

- If a data point does not change the performance if it is added to any subset of the training data, then it should be given zero value.

- When two data points ($i, j$) individually added to any subset of the training data always produce precisely the same change in the predictor’s score, then they should be given the same value by symmetry.

- When the overall prediction score is the sum of $K$ separate predictions, the value of a datum should be the sum of its value for each prediction.

These three properties listed above actually pin down the form of $\phi_i$ up to a proportionality constant.

Any data valuation $\phi(D, A, V)$ that satisfies properties 1-3 above must have the form:

\[\phi_i = C \sum_{S\supset D-{i}}\frac{V(S \cup {i}) - V(S)}{\begin{pmatrix}n-1\\\vert S \vert\end{pmatrix}}\]where the sum is over all subsets of D not containing i and C is an arbitrary constant. We call φi the data Shapley value of point i.

The choice of $C$ is an arbitrary scaling and does not affect any of our experiments and analysis.

Approximation

The main challenge here is the computation of the Shapley value, where the number of data points $n$ has exponential complexity. To circumventing this problem, we can use two methods:

- Monte-Carlo: * “…in practice, we generate Monte Carlo estimates until the average has empirically converged.”*

- Truncation: * “… it is sufficient to estimate the data Shapley value up to the intrinsic noise in V (S), which can be quantified by measuring variation in the performance of the same predictor across bootstrap samples of the test set (Friedman et al., 2001). On the other hand, as the size of S increases, the change in performance by adding only one more training point becomes smaller and smaller (Mahajan et al., 2018; Beleites et al., 2013). Combining these two observations lead to a natural truncation approach.”*

Applications

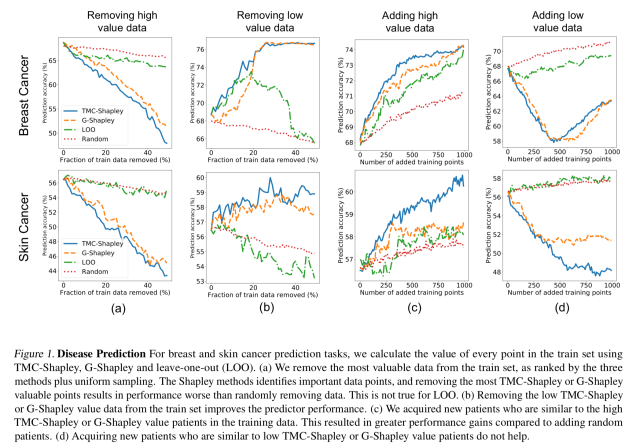

The main test case James Zou presented at a talk was using the UK Biobank data set and model to predict breast and skin cancer. As we can see in the graph below the effect of data points are taken away from the training data, starting with the most valuable data points.

If we go in the other direction and start by removing the lowest valued data points, the model performance improves! Points with a low Shapley value harm the model’s performance and removing them improves accuracy (Fig 1b above).

If we wanted to collect more data to improve, then adding data points similar to high-value data points (assuming that’s something we can control in data gathering) leads to much better performance improvements than adding low-value data points (Fig 1c and d above).

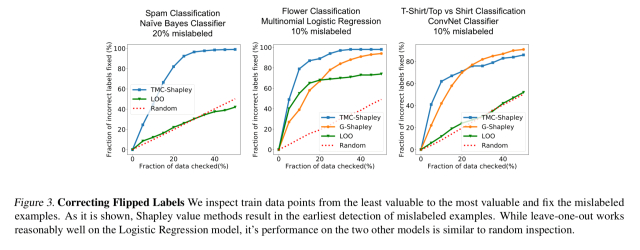

Another experiment trained data with noisy (incorrect) labels and found that the erroneous data points ended up with low data values. Thus by inspecting data points from least valuable to most valuable, you can likely find and be able to correct mislabeled examples.

Conclusion

Data Shapley uniquely satisfies three natural properties of equitable data valuation. There are ML settings where these properties may not be desirable, and perhaps other properties need to be added. It is a very important direction of future work to clearly understand these different scenarios and study the appropriate notions of data value. Drawing on the connections from economics, we believe the three properties we listed is a reasonable starting point.