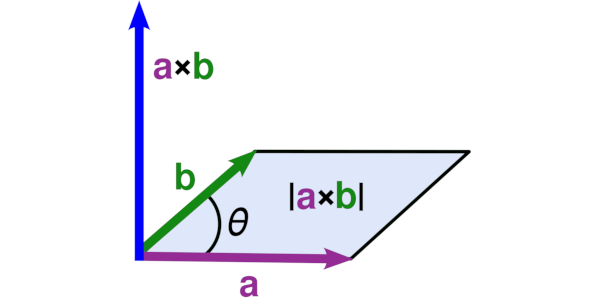

A normal to a pair of vectors is a vector that is at the right angle to both of them so that a normal to a plane is a vector that is at the right angle to all the vectors that are in that plane.

Finding normals will enable us to communicate numerically about many real phenomena, including rectangular constructions and the reflections of rays of light from surfaces. The key to all these possibilities is the technique based on the vector multiplication, termed the vector product of vectors (since the result is itself a vector) or the cross product of vectors (named after the cross notation used).

The Cross Product has an excellent graphic interpretation and is quite similar to that of the determinant, as covered in a previous post.

Just like we find the determinant after a transformation, we also see the cross product after a transformation. This means orientation could be flipped, just like turning a paper over is the equivalent of flipped orientation.

If we remember from linear algebra, a vector has a tail and a head. Anytime we have two vectors $\vec{v}$ and $\vec{w}$, taking the cross product $\vec{v} \times \vec{w}$ results in pacing a copy of $\vec{v}$’s tail on $\vec{w}$’s head and a copy of $\vec{w}$’s tail on $\vec{v}$’s.

So every time we are taking the cross product, we can imagine, at least in 2D, that we have this geometric interpretation — and have a visual sense of what we are computing. If it wasn’t apparent to you by now, the cross product computation is much like the determinant, as we are finding the area of this area.

And the computation? Just as easy as the determinant:

\[\vec{v}\times\vec{w} = det\left(\begin{bmatrix} v_1 & w_1 \\ v_2 & w_2 \end{bmatrix}\right) = v_xw_y-w_xv_y\]So we take $\vec{v}$’s first coordinate times $\vec{w}$’s second coordinate minus $\vec{w}$’s first coordinate times $\vec{v}$’s second coordinate. The sum of that is the sum of the cross product.

Cross Product in 3-Dimensional Space

\[\begin{bmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ v_3 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ w_3 \end{bmatrix} = det\left( \begin{bmatrix} \hat{i} & v_1 & w_1 \\ \hat{j} & v_2 & w_2 \\ \hat{k} & v_3 & w_3 \end{bmatrix}\right)\]Which is equivalent to

\[\hat{i}(v_2w_3-v_3w_2)+\hat{j}(v_3w_1-v_1w_3)+\hat{k}(v_1w_2-v_2w_1)\]